As a dancer, listening to the body is a big topic of interest to me. I’ve written several posts about this, but a couple years ago I wrote about how hypervigilance and trauma can easily be confused for body messages and “intuition” (read it here), and the ideas in that post have been swirling in my head for a while. I wrote that from a personal perspective, but I’ve wanted to explore how these concepts are represented in the wider culture of healing/wellness spaces, particularly in a Western/North American context. Filtered through hyper-individualist values, intuition and body knowledge often become ways to maintain separation and an illusion of control, leading us to analyze others from a distance and cope all alone with things humans have always navigated in community. My own perception of intuition/body wisdom has changed considerably over the years, and I’ve developed a model to compare and differentiate hypervigilance and over-intellectualization from healthy, balanced intuition that involves deeper intimacy with the body and the outer world. Read on for more!

*Please note that although I discuss psychology and therapy-related terms like hypervigilance in this post, I am not a licensed therapist or clinician. I am an educator/artist with training in somatic tools, and this is my lens.

Intuition as a Muscle

First and foremost, I see intuition as a type of muscle – and as such, just as natural and with similar patterns to our other physical muscles. Observation is the way it is exercised and toned, and like our other muscles, it is designed to attune and respond both to what’s going on within our bodies and the outside world. Our muscles help us literally move our bodies and hold our structure together, and they also help orient us in space by allowing us to sense where our limbs are. Developed and conditioned properly, intuition does much the same thing: it helps us navigate complexities of life that go beyond basic instincts, it holds our psyche together, and it gives us a sense of ourselves in relation to others. However, a muscle that’s out of balance can create problems in the whole system. We usually think of weak or atrophied muscles being the problem, but over- and under-developed muscles are two sides of the same coin: they are both out of balance, and they typically occur together. An over-developed muscle is not a super strong, all-powerful muscle: it’s a dysfunctional muscle that is not being used properly and can majorly destabilize our body over time. Wellness spaces tend to present intuition as a muscle that just gets infinitely stronger in ways that are only ever beneficial, but that’s not what I see to be the case. Over-development and over-use of intuition as a muscle creates dysfunction in our psyches and lives. It will tend to take over and pull other things out of alignment, disrupting how we sense ourselves and the world, and inhibiting (or even atrophying) other muscles like communication and relational skills.

The Intuition Spectrum

Intuition uses the body, mind, and emotional landscape to respond to cues from the present moment. The present is always in flux and because it’s perpetually unfolding, it’s also uncertain: so, our intuition is ultimately based on our capacity to be intimate with the uncertainty of the now.

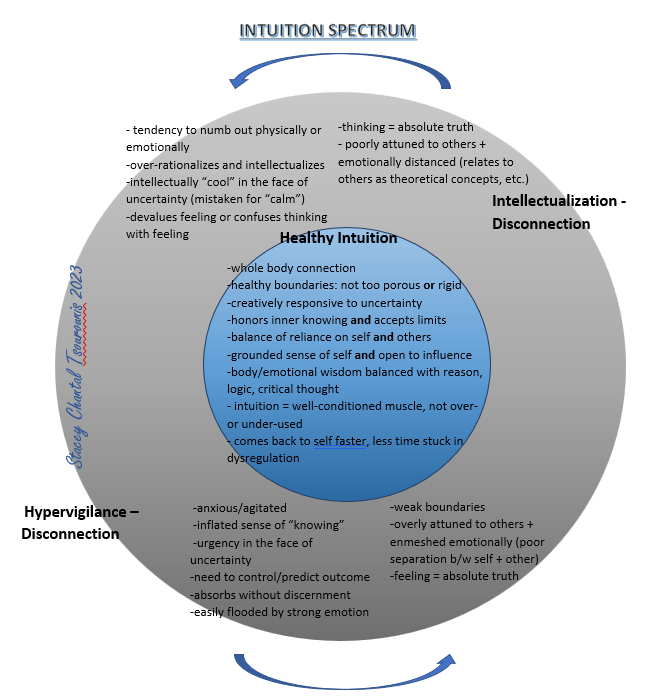

I don’t see this as a linear spectrum, because I don’t see these different facets of intuition as progressing in a linear way. I have instead conceptualized this as a circle/sphere: the core represents actual healthy intuition as a properly balanced and conditioned muscle, whereas the outer layers of extremes represent disconnection from self and others. The two extreme states of disconnection are like two sides of the same coin: people have a tendency to spiral back and forth between them, without truly settling into the core of healthy intuition. Here is how I have come to understand these different layers and how they enhance or sever connection to the body and others:

The Extremes of Disconnection

Over-intellectualization

In this state, people seek refuge in the mind and find ways to leave the body behind. They may find ways to numb emotions and bodily sensations, like compulsive scrolling on social media, drinking too much, over-eating, etc. They can come across as cool and rational, and accumulating knowledge helps them feel in control in the face of uncertainty. They may devalue emotion and the body (not necessarily consciously), and drown out prompting that might be valuable information. They can also conflate intellectual knowing with expertise and practical experience. They can have overly rigid boundaries, with little capacity to adapt and flow based on changing circumstances. They tend to be disconnected from others, and use intellectualization as a stand-in for intimacy. For example, they may interact with others more like theoretical concepts than people – learning their attachment style, enneagram, Human Design chart, etc. and then using these profiles to attempt to predict someone’s response or try to understand their inner landscape without actually involving the other person in the process. Ultimately, this amounts to knowing people and knowing the world in general from a distance: sticking to theories and models is a way of feeling safe and in control. Because over-intellectualizing leaves little room for emotion, the body, and sensing the present moment and uncertainty, it isn’t true intuition.

Hypervigilance

The complementary extreme (notice I didn’t say “opposite” extreme!) involves an intense experience of emotions and body sensations. People in a hypervigilant state are easily flooded by both their internal sensations and what they take in from the world – and they tend to absorb so much it’s difficult to manage. They have very porous boundaries that lead to enmeshing with others, and have trouble discerning what feelings actually belong to them and which are from the outer world. They are overly attuned to others’ emotions, and compulsively try to read people to understand them, anticipate their needs, or predict what comes next. Being so enmeshed emotionally with poor boundaries keeps people just as disconnected from others as over-intellectualizing: “reading” others or situations is a way of making sense of people and the world from a safe distance. People with a strong tendency for hypervigilance often consider themselves “highly intuitive”, and this is where messaging of the wellness industry can be detrimental: because their emotional experience is so intense, hypervigilant people lend extra weight and validity to their feelings. Everything feels big and deeply personal, and messaging like “your intuition never lies” makes it easy to think that the stronger and more intensely they feel something, the more true it must be. This makes them feel staunchly certain and in control. Because there is little room for uncertainty, and they are disconnected from their bodies, others, and the present moment, this is also not true intuition.

The Dance Between the Two

Although I think most people have a tendency to fall into one pattern more than the other, over-intellectualization and hypervigilance are not fixed states: people swing back and forth between them. Hypervigilance is an overwhelming state to be in, and though it can feel like an intense rush, it gets exhausting….and when it does, people will numb the big emotions and body sensations for relief and swing into over-intellectualizing. After a while, they may crave more intensity, or something happens that gets them very emotionally activated, and they swing back again. Both in myself and many others, I’ve seen that these states complement and feed off of each other in this way.

Neither of these states is fixed and neither is “bad” – they both have their place in our lives and can be useful, and they’re not states you’ll transcend by doing enough “healing” or working on yourself. You may need to go more heavily into rationalization when it’s not wise, safe, or helpful to actually go too deeply into your emotions. Sometimes you just need to do the damn thing and process later (and not everything necessarily needs “processing”). Sometimes leaning into reason as a counterbalance to heavy emotion can bring much-needed clarity. Hypervigilance has its place, too: threats and danger are a reality of life. Levels of threat are not equal among all humans, either – the more marginalized someone is, the more threat they are realistically exposed to compared to someone else. We can certainly do all we can to create safety around us, but complete safety is a fantasy: we’re animals on a changing, unpredictable planet, and we evolved survival responses for a good reason. This is not an either/or concept, but a both/and: extremes of rationalizing and vigilance are sometimes necessary, AND living in these states as a default setting will have consequences. It will be hard to fully engage with others and with life, and spending more time scanning for threat than building connection will create a lack of strong community. This tendency also takes us out of the uncertainty of the present, which is where our powers of observation and attunement work with our body as intuition. The more these states are over-used, the more they can lead to retreating from life and collapsing in on ourselves, reducing our world to only what lets us feel total control. Ultimately the only way for your intuitive senses to always be right is to never open yourself up to life enough to be wrong.

Healthy Intuition: Inner and Outer Connection

As a healthy, well-conditioned (but not overused) muscle, genuine intuition presents quite differently from over-intellectualizing or hypervigilance. To me, the most significant difference that characterizes healthy intuition is that it has a spaciousness to it – there is room for the unknown, for contradiction, for being wrong, and for accepting outside influence. The very idea of accepting outside influence can be confronting to people in the intellectualizing/hypervigilance spiral, as both these states involve a high need for control, and outer influences are outside our scope of control. But really, influence is at the heart of true intuition: we observe and take in data from the world and people around us, and our body pieces things together, often using clues we may not have consciously noticed. This process requires engagement with life, not total retreat from it. This kind of engagement requires both a steady sense of self as well as interconnectedness. In this state, we are not stuck in overly rigid or porous boundaries – we are clear about them but also responsive and adaptive to how people and situations may change. There is trust in our own knowing, but without the grandiosity of needing to believe we can know it all by ourselves: there is a healthy sense of our own limitations, and we can seek outside input, guidance, or expertise without it shaking our confidence. We can use and trust our discernment about where and from whom we seek input, and we can accept influence as a form of healthy interdependence, even if it involves difference and disagreement. Emotions and body perceptions are valued and respected, but importantly, they are seen as data, not direction – while informative, we can accept that our emotional experience does not necessarily reflect objective truth, and we can bring in rationality, critical thought, and other viewpoints to deepen our understanding. This is especially true when we are responding emotionally in relationship with another person: genuine intuition has space for shared meaning-making and vulnerably communicating with others rather than deciding what they feel and think and what it means all by ourselves. Lastly, this state is not a static endpoint we reach: it’s a dynamic experience that still has space for more extreme rationalizing or vigilance when necessary, without getting stuck and staying in the spiral.

Western cultural influence: thoughts and questions

As I’ve been reflecting on intuition as intimacy, I’ve also been thinking a lot about how these states of connection vs. disconnection are viewed and spoken about in online healing spaces that are disproportionately white, Western, and hyper-individualistic. Western ideals (and a strong streak of North American puritanism) have a palpable influence in online wellness and “healing” culture, and our understanding of everything we learn is filtered through it in ways that I rarely see spoken about or interrogated (not by Westerners themselves, anyway). When it comes to intuition, much of what I’ve described in this post may feel odd filtered through Western values. Emphasizing the self and prioritizing control and solitary meaning-making are idealized in a Western hyper-individualistic mindset – in fact, a great deal of what I read about intuition and healing in general glorifies collapsing into oneself and even lauds it as a sign of evolution. How often do we see things like “the more you heal, the less you end up liking people”, or messages about distancing ourselves from people at the first sign of conflict to “protect our peace”?

These values come through strongly in our cultural understanding of the concept of intuition. The over-intellectualizing/hypervigilance spiral is naturally conflated with “strong intuition”: being set apart from others and developing intuition to the extent that you’ll never need to rely on or listen to anyone else is framed as an ideal to strive for. Intuition is even wielded defensively as a coat of armor or a way to subtly threaten people into behaving the way we want them to: telling people we’ll always know if they’re lying or not saying something because we’re so intuitive (so don’t even try it!) is an attempt to have full control in the relationship. But control and intimacy can’t really co-exist, and emotional safety is co-created, not just something other people prove they can provide to us. I’m not suggesting these behaviours never happen in more communal societies, of course, but I do see that disconnection is often viewed quite differently outside of a hyper-individualist context. Through a collectivist lens, distance and disconnection may seem like a loss of self or identity, or even a denial of social responsibility, rather than states to strive for and stay in.

These things are complex, and obviously Western cultural programming isn’t the only factor here, but it is a significant one that I think warrants being explored and reflected on more deeply. There are so many concepts in wellness spaces that I see being contorted by this messaging, and we’re using everything from intuition to boundaries to attachment theory and more to build individual fortresses rather than bridges of connection.

I know personally that during the period of my life where I strongly identified with being “intuitive”, I actually struggled to have healthy closeness with people. The certainty and control that I attributed to strong intuition could only be maintained from a distance without truly engaging or communicating, and I made many decisions that were based on assumptions. I would have been much better served in so many instances by being curious and asking questions. The curious questions I have now are these:

What if we stopped pretending that we can use things like “intuition” to transcend our need for each other? What if we used intuition to repair and deepen relationships to others and to the world, instead of escaping them at the first hint of discomfort? What if we were awed by all we don’t and can’t know alone rather than being threatened by it? What if instead of collapsing into false control by ourselves, we learned to vulnerably face uncertainty together?

As always, thank you for reading and I welcome your thoughts, feedback, and questions! In Part 2, I apply this model to a case study example, so read on if you’re curious.

I especially like your last question: What if instead of collapsing into false control by ourselves, we learned to vulnerably face uncertainty together?

LikeLiked by 1 person